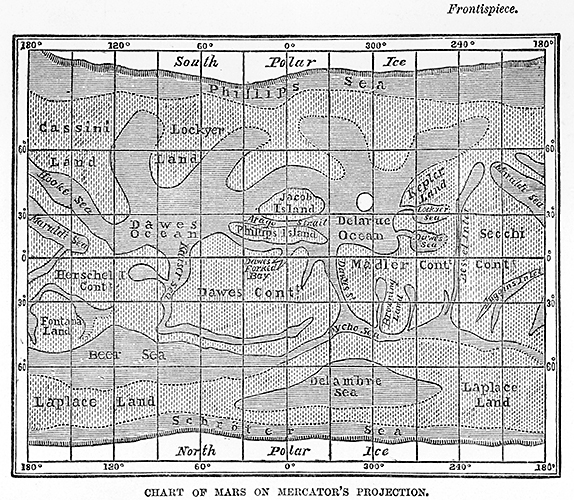

When German astronomers Wilhelm Beer and Johann Madler first applied a latitude/longitude graticule to Mars in 1840, they essentially created a base map for other observers who could then add detail from their own observations after each biennial observation season. The expectation from that point forward was that all observers of Mars should see the same features on Mars, in the same places on its surface, time and time again. Individual observations from multiple viewings could thus be incorporated into a composite map that represented a sum total of scientific knowledge about the Martian surface.

As astronomers added new detail to the Mars map throughout the 1860s and 1870s, a significant popular interest developed around the landscape and geography of Earth’s neighboring planet. I argue that this interest developed largely because of the way the planet was mapped. The primary views preferred by the astronomer-cartographers of Mars were the Mercator [fig.2] and stereoscopic [fig.3] projections. The Mercator projection was then very well known as a navigation map. Although Mercator maps introduce significant distortion of the shape and area of polar and sub-polar latitudes, their straight lines of latitude and longitude allowed explorers to orient themselves to the map by cardinal direction.